Because we’re examining some of the biblical foundations of dreams today, I’ve been thinking a lot about just how significant dreams are to our lives and how meaningful they can be to us when we’re awake. So, when we were coming home from Ireland on the plane and John had fallen asleep beside me, I decided this would be an opportune time for me to test out just how easy it is to manipulate a person’s dreams while they’re sleeping.

Because we’re examining some of the biblical foundations of dreams today, I’ve been thinking a lot about just how significant dreams are to our lives and how meaningful they can be to us when we’re awake. So, when we were coming home from Ireland on the plane and John had fallen asleep beside me, I decided this would be an opportune time for me to test out just how easy it is to manipulate a person’s dreams while they’re sleeping.Now, as weird as this seems, scientists and other, more morbidly curious types, have been conducting experiments just like this for about the last two hundred years in an effort to determine just what our dreams mean and how they are affected. Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud had a bit of a rivalry about this topic, and even researchers today are unsure about whether your dreams are a reflection of hidden and repressed desires or whether or not they’re the cause of some of our more abstract actions in waking life.

What we do know consists of a scientific field known as oneirology, dream research, which is predominatly concerned with R.E.M. sleep, rapid-eye-movement sleep, or “dream sleep.” This is the lighter, latter, portion of the sleeping stages in which we experience our dreams. Now, for a typical adult we spend about 20% of our sleep time dreaming, maybe 90-120 minutes per night; but this number decreases the older we get. What I find really interesting, however, is that it has been decreasing ever since we were first born – such that babies dream 80% or more of the time and there are theories that suggest they even dream in the womb or that the womb itself may be an unbroken cycle of R.E.M. sleep.

This is such a great picture for us of the sweetness and innocence of the infant mind, and the inborn hope with which we come into this broken world. It may just be genetics that cause us to dream less as we get older, but it may also be a representation of the fact that the damaged condition of our culture actually pulls us apart from the innocence with which we’re born.

One notion about dreams that has recently taken off among the scientific community is the idea that dreams are a kind-of mood regulatory system, like a built-in therapist. In this theory, dreams give us an avenue to get out our negative and wanton whims so that they aren’t forced to come out in waking life and disrupt our social order, friendships, vocations, or connections with the world around us.

In scripture, there are two terms that are used to reference dreams – dreams and visions – both of which were thought by the people of the ancient near east to be means by which God spoke to His people. Both dreams and visions fell into the category of oracles and/or prophecies, and there was a large weight and emphasis placed upon their interpretation and recollection by magi and scholars. Visions, which are simply dreams one might have in the day – either waking or napping – and dreams were considered to be the actual voice of God and magi sought His guidance in a practice known then as “dream seeking” in which they would place themselves purposefully asleep in an attitude and atmosphere of prayer and fall away asking God to reveal Himself.

In the Bible we have many great dreamers, and today I’d like to draw a connection between two of the more prominent, one from each testament, Daniel – the RabMag in Babylon – and the apostle John – an exile on the Greek island of Patmos. The connection I’d like to make has to do specifically with Babylon, and Babylon as a symbol within dreams.

For Daniel, Babylon was a symbol and a reality because he was a Jewish man living in exile in the court of the king. He knew what Babylon was like in real life, but also knew that Babylon was a symbol for his people of the corruption of a foreign ruling authority that dominated and oppressed the Israeli people.

For John, Babylon was only a symbol because it had ceased to be among the significant world powers at the time. Yet, having passed from present reality into myth, Babylon arguably became an even greater symbol of an evil power that had once oppressed the Jews and from which they had subsequently been freed.

For both men, and for us in our practice of interpreting scripture, Babylon is importantly understood as the dominant socio-economic, cultural, and political power of its day. So, for Daniel Babylon was both dominant in reality and in prophecy as a means of diving the future fall of a future Babylon; and, for John, Babylon was an excellent way of referring to the Roman Empire and the coming persecution of the Church and a powerful futuristic insight into the final triumph of Jesus Christ over the powers of this world.

But what does that mean for us?

Who is our Babylon?

Well, a more accurate question might be “who is the dominant socio-economic, cultural, and political force in our world?” and one answer might be “the West.” Now, let’s make sure that everyone understands me correctly because I’m certainly not making a one-to-one connection between the United States and Canada and Babylon in the book of Revelation; what I am saying is that we need to ask ourselves what kind of world we live in and whether or not it is a world that reflects the law of love or the laws of power.

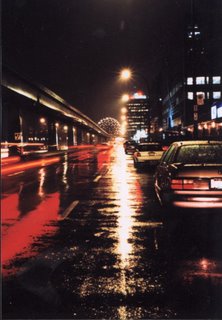

I submit that our world, by-and-large though exceptions are everywhere, is a world governed by power and oppressive of love. And not only is that power dominant, but it is seductive – the lure of easy money, easy sexual fulfillment, and ever-increasing power calls to us which is why Babylon is described in Revelation as a Whore.

Because Power is seductive.

I think we live in a world where love is a fledgling ideal and the great machine of war chews on it daily…

And it’s our job to fight that machine with love.

There’s a powerful section in Revelation 18, which is really my motivation for talking about all of this today, where the angels of God announce to the world that Babylon is fallen, and the truly breathtaking sequence inherent in that fallenness is the tidal wave of simultaneous lamentation and rejoicing.

The angels rejoice.

And everyone in bed with the whore weeps.

Because now, finally, the rule of love has surpassed the rule of power and love has itself been vindicated as the greatest power. All those who have profited by subverting the weak and feeding on the poor are now toppled by the triumph of God, and all those who’ve lived as agents of love are free to love more now that this time has come.

For us, we’re left with a powerful set of questions. First, we’re left wondering if we can be honest about which side we’ve chosen. Money, after all, isn’t evil, and neither is power nor sex, nor a host of things that have been twisted by darkness. And having money, or being concerned with money, isn’t necessarily an indication of our allegiance to Babylon; rather, being consumed by Money, loving Money, and serving Money – these are the signs of false allegiance.

When we rack our minds for greater profit and cut ethical corners to increase our gains, then we have legislated ourselves in Babylon.

But when we hold everything loosely, as a gift from God that we are eager to use as a measure of His blessing, we reflect His heart and are governed by Love.

Which takes us to our second question: what will our reaction be when Babylon falls? Will we rejoice now that the kingdom of Love is established, or weep because our opportunities are at an end?

There was a trememdous book written a couple of years ago entitled “Mustard Seed Vs. McWorld” by Tom Seine which talked about how we might use wealth and influence to promote equality and free others from debt and the constraints of low-birth, and if you’re interested in this kind of thinking I suggest you give it a glance. For those of you more poeticly inclined, have a peek at Conversations with Bono by Michka Assayas and allow him to speak to your soul about making poverty history and the role of the privileged west in that process.

Finally, the question we are forced to ask is about where we have invested ourselves. Have we placed our seed in an economy of faith or a culture of greed? And, are we courageous enough to mold our dreams elsewhere?

The word courageous, by the way, comes from the french word “coeur” which means heart. And our measure of courage is always a measure of what we truly love and believe in.

Which brings us full circle back to our discussion about dreams – about where our hearts are at and what we value most.

If you’re like me, the most precious thing in all the world is Carmel and Jacob [though, for you, those names ought to be different]. My wife and son, and Anna – our daughter-to-be. And all my dreams are full of hope for these three, for their future with Jesus and the adventure of their lives that will enable them to touch Him, however briefly.

Even now I can close my eyes and see myself about Jacob’s bed every night, placing my hand on his forehead and kissing him softly praying that God would watch over his dreams and protect his heart. That he would cultivate a love for the Word and a love for Worship and that Jesus would always be held closely in his heart and that he would remain sensitive to the Holy Spirit and obedient to the prompting of God.

And that’s my prayer for you – that your dreams would be sweet and your knowledge of Jesus a special knowledge. I dream that you would know God better than I and help me to get another piece of Him.

Good night.